Festivals as influential testing grounds for circular regions & cities

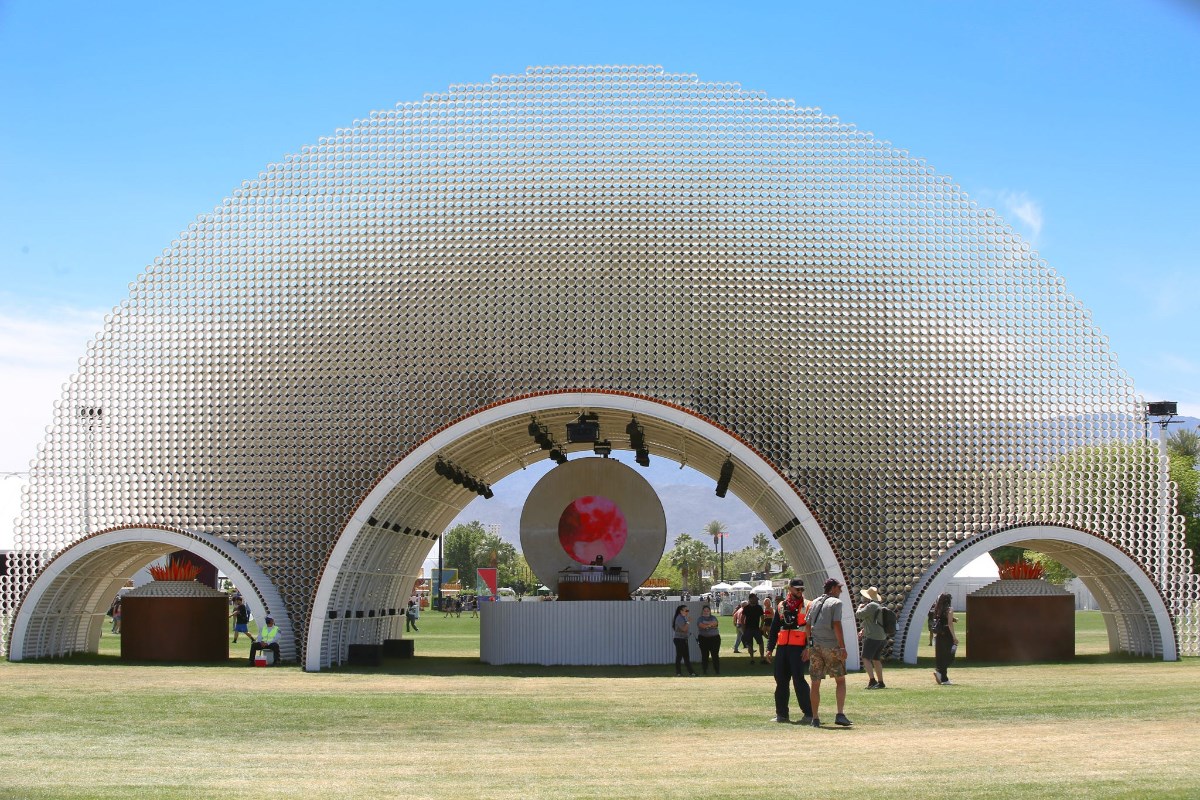

This article was originally written by Bram Merkx and published here by Circular Festivals. Header image: Brian Blueskye (Coachella, 2022).

Daniela Berenguer from Radboud University (Nijmegen, The Netherlands) did a research on how the festival scene can contribute to circular and climate neutral regions, cities and neighborhoods. For this article we asked her to share the most important outcomes.

Many of us working in festivals and events know that festivals are a great place to test innovations and try new ways of doing things. Daniela Berenguer from Radboud University (Nijmegen, The Netherlands) did a research on how the festival scene can contribute to circular and climate neutral regions, cities and neighborhoods. She followed circular solutions and innovations from festivals, and watched how they scaled-up from the festival to open-city events, and finally to cities.

For this article we asked her to share the most important outcomes, and to have a chat with us about how governments can benefit from both the technological and social innovations that originated in the festival scene.

Q: Why are festivals good spaces of experimentation?

A: “Tijl Couzij, sustainability consultant from LabVlieland and organizer of Into the Great Wide Open festival, explains it best: “Festivals are good for 3 things: as laboratories – to test and learn, as mini-cities – catalysing for circularity in urban systems, and as stages- to inspire others to engage in circularity.”

The main theoretical arguments for why festivals are prime spaces for urban experimentation are:

Their adaptive infrastructure and staff

Due to the temporary nature of festivals, their infrastructure systems are usually external, which means that it is much more accessible for testing innovations than permanent infrastructure in cities, which is normally underground. Festival staff is also very flexible, since they are used to working in dynamic environments where problems can arise and need to be fixed on-the-spot; this means they are less resistant to having to change how they interact with systems or how they do things, making the human component more adaptable than in cities which have very systematic ways of doing things, which is normally a huge barrier to change.

They have the same needs and share supply chains with cities

Festivals can be compared to mini-cities, since they have to provide the same functional systems for their visitors than cities do for their citizens – food and drinks, water, sanitation, mobility, waste management and security- but for huge numbers of people concentrated in a limited time frame. This means that they usually use the same suppliers that provide these services for cities.So any advances that are made in the way festivals provide these systems, especially in more circular and sustainable ways, can immediately be applied to the supply chains of cities. In this way, festivals can act as catalysts for circularity in cities, by testing out innovations and then driving the implementation of those which work throughout larger urban systems.

They have the power to impact both suppliers and consumers in urban environments

Finally, one of the most valuable opportunities festivals offer is the huge reach they have due to the number of visitors they attract. They provide a temporary, alternative, and fun reality for their visitors, which makes them much more willing to try out new innovations than in their everyday life. This creates subconscious connections between circular solutions to good experiences at the festival, which makes them much more likely to adopt these solutions in their normal life. Since they attract thousands of visitors, festivals are also great platforms to showcase circular innovations, showing suppliers and other industries what solutions are possible and inspiring them to adopt them, bringing these innovations into the mainstream much faster.”

Q: Can you give some examples of events that really influenced local policy making?

A: “It’s clear why festivals can benefit from developing good relationships with their local municipalities. However, participants of the Green Deal Circular Festivals, usually sustainability experts in their field, are great examples that highlight why these relationships can also be great opportunities for local governments.

In the UK, Shambala festival has been key to helping develop the Green Event Code, which aims to develop shared sustainability standards and targets for events throughout the whole UK, and to promote the circular best-practices the festival has been working on..

In Groningen, ESNS (Eurosonic Noorderslag) and three other major event organizers partnered with the municipality to create the GROENN coalition. This initiative is a great example of the transformative potential of these relationships. It stemmed from tensions from the government setting strict regulations that initially only hindered events and innovation, but due to open-mindedness from both parties, it developed into a groundbreaking collaboration that is now working to make events in the overall region more sustainable.

In the Netherlands, DGTL has played a key role in the scaling-up of Semilla Sanitation, an innovative water treatment solution that is using festivals to develop and perfect a circular sanitation system, aimed to improve conditions and provide water at refugee camps and disaster areas (the research project of Daniela closely studied this innovation). DGTL festival has been very active supporting Semilla on a Circular Chain subsidy offered by the Dutch government, in order to overcome regulations that currently blocks them from being fully circular. This not only helps the innovators achieve their humanitarian goals, but also paves the way for other circular innovations to have less obstacles in terms of outdated regulations, driving the transition to fully-circular systems.”

Q: Are there any innovations that originated in the festival scene, and contributed to the circular transition?

A: “Definitely! Greener is a green-powered mobile battery solution that was born in the festival industry in 2018. They tested and perfected the technology in the festival industry with Innofest, and have since broadened and become common-place in many other industries like construction, transportation, solar parks, sports events and housing- basically, anything that requires mobile power provision.

This is a particularly interesting example, as it showcases how important collaborating with governments can be: the success of Greener was in a large part because it coincided with regulations from the Amsterdam municipality which required all events to use renewable energy by 2020. This drove the adoption of the mobile battery within the events industry, which allowed it to develop their solution in this innovative environment and finally make emission-free mobile power a reality in places that might not have ever taken that leap. Greener has now started scaling-up by partnering with large renewable energy companies, and going forward they are focusing on flexible energy storage to accelerate the energy transition in the Netherlands even further.”

Q: What we can learn from the outcomes of your research, and how can both festivals and cities apply this in practice?

A: “The main lessons this research found have to do with the importance of identifying circular solutions that can positively impact our existing urban systems, and really focusing on scaling them up to maximize their impacts.

I say solutions, rather than innovations, because I identified a concern that is all too common when people think about transitions: there is too much focus on innovation just for innovation’s sake, thinking it will solve all problems. Participants of the GDCF agree that this blind faith in innovation is spreading limited resources thin, and they believe that “the solutions are already out there, we just have to tap into them” and make them more accessible. Therein lies the importance of stimulating solutions (old or new) that have the potential to transform current systems and bring circularity into our everyday lives. I have developed a methodology to identify solutions with this “transformation potential”, which can be integrated into GDCF’s list of tried and tested solutions. Festival organizers can use this list in a “demand-driven matchmaking process” to select which solutions to implement in their own events. Ideally, they can now work with solutions that will solve their operational challenges while taking a more conscious role in furthering circularity in wider urban systems. Festivals that are currently not participating in the GDCF can also join the pledge and, coming all together, start using the power of the festival industry to demand larger-scale change from large festival suppliers.

Regions and cities across Europe can also adopt this demand-driven matchmaking to solve their own challenges, to engage their citizens, and become circular and climate neutral. An example is what the Amsterdam Innovation team has done in their circular living labs and in the organization of an innovation relay-race towards SAIL Amsterdam, a huge open-city sailing event that will take place in the city in 2025. They can play a huge role in the development of these circular solutions by acting as a “first customer”, and motivate other suppliers to pursue similar solutions by stimulating this sort of circular procurement in the city’s supply chain. They can also support the scaling-up processes of circular solutions more broadly, by removing regulations that act as barriers to circularity and providing circular infrastructure in urban systems. Finally, they can strengthen their role as facilitators, connecting innovators and owners of these solutions to investment-ready programs that offer them the financial and organizational support necessary to reach the mainstream, where their impact can be maximized.”